From Programs to People: The FY2024 Appropriations Process

Updated July 27, 2023

Author: Ross Brennan, Senior Legislative Affairs Associate (ross@progressivecaucuscenter.org)

Introduction

Congress is determining how the federal government will spend—or “appropriate”—its money in the coming year. The Fiscal Year (FY) 2024 appropriations debate occurs as states build a patchwork of abortion policies in the post-Roe v. Wade environment; the conflict in Ukraine continues; and Americans cope with climate change-related natural disasters, among other issues. It also marks the first year that appropriations will be subject to spending caps mandated by the Fiscal Responsibility Act (Public Law 118-5), which limits federal spending while suspending the debt limit. This explainer describes the appropriations process taking shape for FY2024, key changes to that process this year, and the impact lawmakers’ spending decisions may have on the public.

Why the Appropriations Process Matters

Why Agency and Programmatic Funding Matters

Why Conditions and Requirements on Programs Matter

The Appropriations Process for FY2024

New Spending Caps

Where FY2024 Funding Will Go: House vs. Senate

Supplemental & Emergency Appropriations

Community Project Funding in FY2024

Policy Riders in FY2024

Why the Appropriations Process Matters

Every year, Congress passes appropriations bills to fund the government. The appropriations bills fund the discretionary portions of the federal budget, such as education, defense, and housing. Appropriations bills do not include mandatory spending such as Medicaid, Medicare, SNAP, and Social Security. The appropriations process impacts nearly every department and agency across the federal government. On top of that, states and localities often rely on federal funding to carry out projects in their jurisdictions, like public health campaigns or transportation upgrades. The amount of funding Congress appropriates for federal agencies and programs, as well as the conditions on that funding, can have tremendous effects on working families.

Why Agency and Programmatic Funding Matters

The level of funding each federal department or agency receives impacts its ability to execute its mission. For example, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) carries out the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which provides healthy food and nutritional services to low-income pregnant, postpartum, and breastfeeding individuals and children under five. House Republicans’ proposed FY2024 funding bill for USDA cuts WIC by $185 million, which is the lowest allocation since 2006, and drastically slashes the program’s monthly fruit and vegetable benefit potentially impacting 5 million toddlers, new Moms, and pregnant individuals. Families have made clear how this change would harm them:

“The increased fruit and vegetable benefits in WIC have been great for a grandmother of three. WIC makes sure that all three kids get the amount of fruits and veggies that they need and love! If this benefit was lowered, it would mean that my grandkids wouldn’t get as much as what the doctors tell me they need. The added benefit also helps me manage my household budget, especially with inflation and the cost of groceries overall. ”

Another example is the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Administration for Children & Families (ACF), which funds Head Start, a bedrock early childhood education and development, health, and social services program up to age five. The House Republicans’ proposed FY2024 funding bill would cut Head Start by $750 million next year, potentially kicking more than 50,000 children out of Head Start.

Families and children, who often bear the brunt of these drastic spending cuts to critical programs, know how much this would impact their daily lives. This story below was provided by MomsRising:

“I adopted my grandkids when they were very young. They spent their earliest years in an unstable household, and Head Start made a huge difference for them. It helped them both flourish and come out of their shell while building the skills they needed to get ready for kindergarten. I chose to volunteer at the program because I saw the impact it had.

Head Start doesn’t just support kids, it also strengthens families and communities. My grandkids got breakfast, lunch and a snack at their program which was a huge help for me as a grandparent trying to make ends meet with disability benefits. We live in a small, rural community; we still run into their teachers and classmates around town, and we cherish those connections and friendships. Our nation’s kids are our future. If we don’t give them a strong start, our country will be worse off. No policymaker should ever consider cutting funds for Head Start because Head Start programs are essential to our nation’s success.”

Why Conditions and Requirements on Programs Matter

Appropriations bills typically fund the government through the end of each fiscal year (September 30). If a new appropriations bill has not been signed into law by that expiration date, Congress must pass a stopgap measure known as a “continuing resolution” (CR) to fund the government at current spending levels. For example, if a CR were to pass this year, it would fund the government at FY2023 levels. Without a new appropriations bill or a CR, the government shuts down. For more information about government shutdowns, see the Congressional Progressive Caucus Center’s explainer, FAQs about Government Shutdowns.

Because appropriations bills must pass to avoid a shutdown, members of Congress may insist on including pet provisions that condition federal funding or require actions by federal agencies in exchange for their votes. These provisions are often called “riders,” as they “ride” into law as part of a larger legislative initiative—in this case, an appropriations bill.

Like funding cuts, riders can have negative implications for the public. For example, since 2012, all federal spending bills have included a rider that bans the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)—a small, independent federal agency that protects workers’ rights to organize and form unions—from using any federal money to establish a new system that would allow “voting through electronic means.” As we’ve discussed in previous explainers, the NLRB is responsible for conducting union elections—also known as representation cases—to determine if workers wish to be represented by a union. The 11 year old rider prohibits the agency from conducting union elections remotely, which was particularly troubling during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and even now as people continue to work from home more consistently. In fact, 35 percent of workers whose job enables them to work from home continue to do so. This rider impedes the NLRB’s ability to carry out its mission and uphold workers’ rights. In fact, the NLRB suspended all representation elections at the onset of the pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the need for alternative forms of union election participation in cases where workplace health and safety risks make an onsite, in-person election unworkable. Electronic voting could also provide an efficient solution for union elections that involve workers at multiple work sites, remote or virtual workers, and those juggling complex work schedules, such as educators, tech industry workers, and service workers, among others. There is already precedent for similar use of this technology: electronic voting has been used effectively by the National Mediation Board for years to collect votes on the resolution of labor-management disputes. There has also been a recent increase in union election activity before the NLRB. During FY2022, the NLRB saw a 53 percent increase in representation cases nationwide. An electronic voting process could help elections move forward in a timely and efficient fashion, providing more certainty for workers and their employers alike. However, the decade-old appropriations rider prevents the NLRB from spending any resources or staff time on this issue, therefore blocking changes that could bolster workers’ rights.

The Appropriations Process for FY2024

New Spending Caps

To begin their work, the House and Senate Appropriations Committees need the topline spending level they will allocate among discretionary programs. To understand how the committees determine those numbers, see Show Me the Money: A Timeline of Key Steps in the Appropriations Process and FY23 Appropriations Explainer.

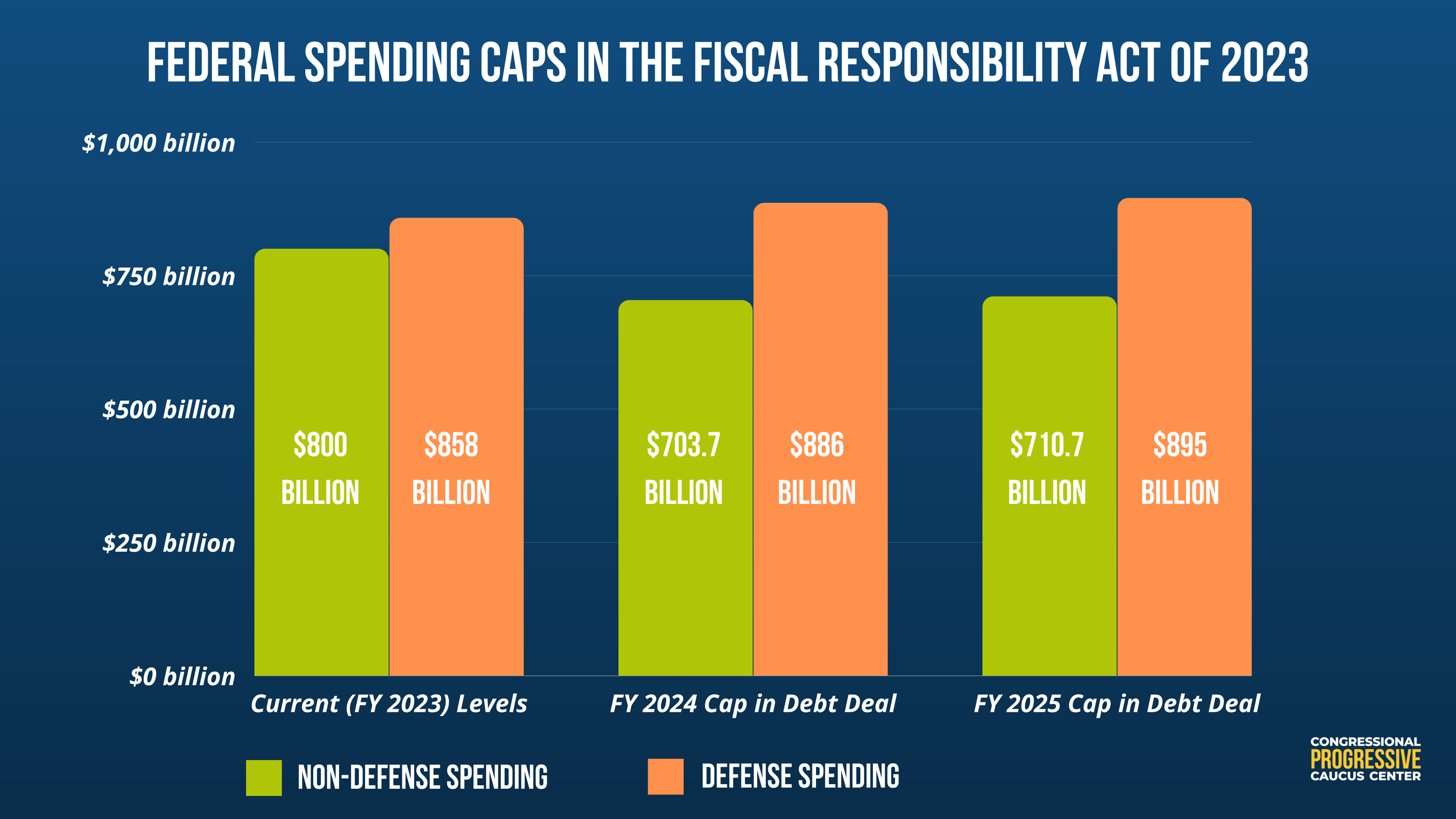

On June 6, 2023, President Biden signed the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, legislation to suspend the debt limit until January 1, 2025, while capping federal defense (DOD) and non-defense discretionary (NDD) spending for FY 2024 and 2025. The figure below illustrates those caps and contrasts them with current spending levels. For more information about the Fiscal Responsibility Act, check out Breaking Down the Debt Ceiling Deal.

The spending limit for FY2024, including both defense and non-defense spending, will be capped at $1,569.7 billion, rising to $1,605.7 billion in FY2025.

Where FY2024 Funding Will Go: House vs. Senate

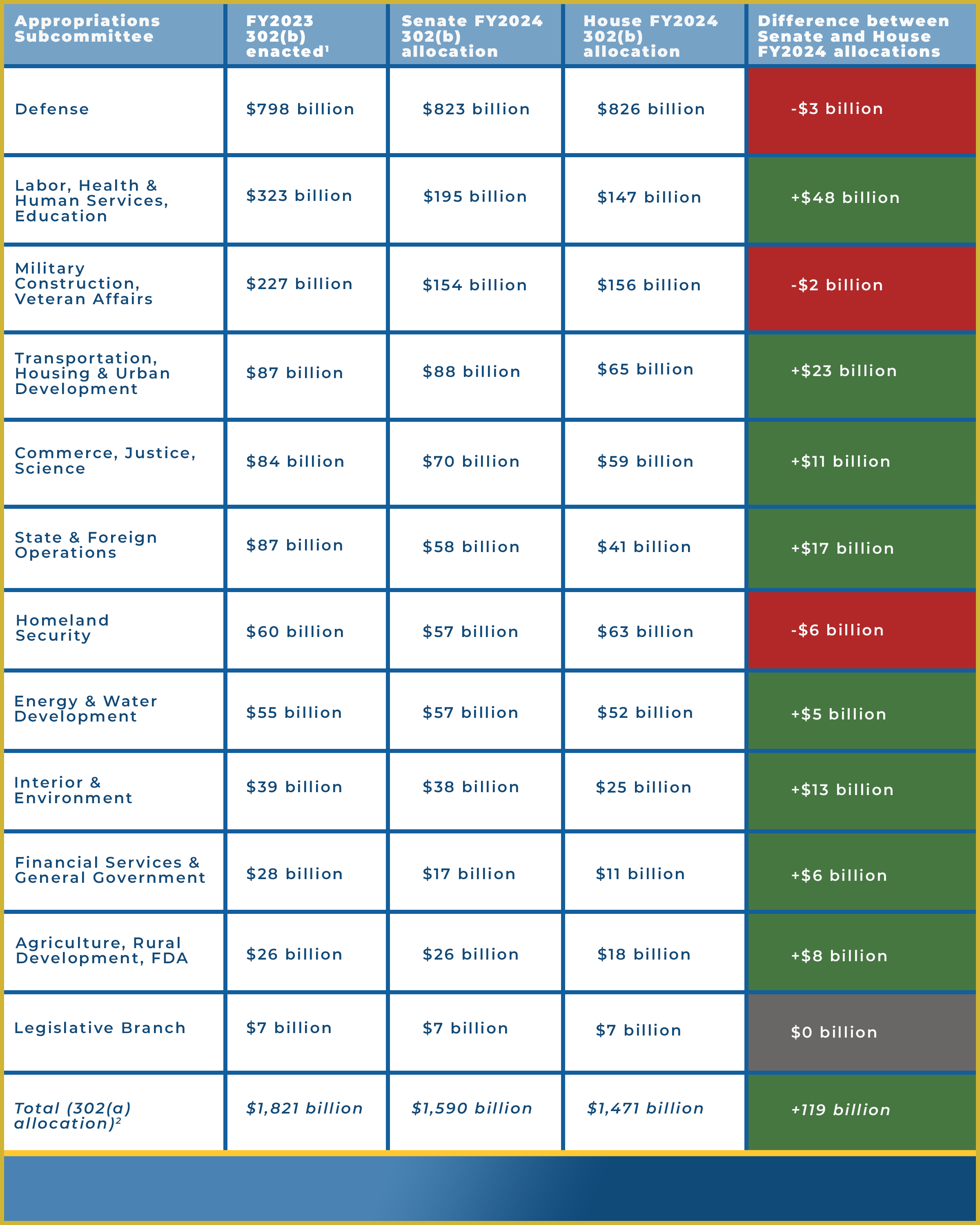

Table 1 below shows how the House and Senate Appropriations Committees propose dividing funding among the 12 appropriations subcommittees—known as 302(b) allocations—in FY 2024, as well as the previous fiscal year’s (FY2023) allocations that were signed into law

Table 1: Comparing Subcommittee Allocations for FY2024

¹Excludes disaster funding outside budget caps.

² Total may not equal the sum due to rounding.

As Table 1 illustrates, the House-proposed appropriations bills total far less than the FY2024 Fiscal Responsibility Act spending cap of $1,569.7 billion for defense and non-defense spending. Further, lawmakers must reconcile the $119 billion gap between the House and Senate’s proposed allocations before the September 30 government funding deadline or risk a CR or shutdown.

Supplemental & Emergency Appropriations

Congress frequently uses supplemental appropriations in emergencies that require funding immediately, such as natural disasters, public health crises, or economic recessions. These supplemental appropriations layer on top of funds already included in the regular appropriations for that year. They are not subject to spending caps, pay-as-you-go policies, or budgetary controls. For example, since the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Congress has passed four supplemental appropriations bills that provided aid to Ukraine. For more information about this aid, see One Year On: The War in Ukraine and U.S. Support.

Some senators have already made a bipartisan deal to pass supplemental funding for FY2024 to sidestep what they argue are too-low spending limits in the Fiscal Responsibility Act. Senate Appropriations Committee Chair Patty Murray (D-WA) and Ranking Member Susan Collins (R-ME) recently announced a deal to add $14 billion for FY2024 spending. Under the agreement, Defense appropriations would receive an additional $8 billion, Homeland Security and Labor-HHS-Education would each receive an additional $2 billion, State-Foreign Operations would receive an additional $1.35 billion, and Commerce-Justice-Science would receive an additional $350 million. This supplemental spending would need to pass both the House and Senate before the President can sign it into law.

Community Project Funding in FY2024

Congressionally-directed spending (CDS), commonly referred to as “earmarks,” is a member-requested allocation of discretionary spending for a specific project, generally within a member’s district. Congress placed a moratorium on this practice in 2011, but reinstated it in 2021.

In the 118th Congress, in which Republicans took over the House majority, both the House and the Senate Appropriations Committee Chairs have continued accepting earmark requests—now called “Community Project Funding”—from members. In keeping with the previous Congress’ CPF rules, members submitting earmark requests must certify that they do not have financial interests in the projects and must make requests public. Members may submit up to 15 funding requests and the earmarks cannot exceed 1 percent of discretionary spending for the fiscal year. The funding is only eligible for government or non-profit entities. For FY2024, House Republicans have requested a total of $10.2 billion in earmarks across 1,864 projects, while House Democrats have requested a total of $9.2 billion across 3,203 projects.

However, House Appropriations Committee Chair Kay Granger (R-TX-12) released guidance that placed some new restrictions on eligible projects. For example, CPF cannot be used for “memorials, museums, and commemoratives (i.e., projects named for an individual or entity).” Further, Chairwoman Granger banned earmarks from the Defense, Financial Services and Labor-HHS-Education appropriations bills. Examples of projects that have previously received funding through these bills—and will be excluded under the ban—include upgrades to hospital equipment, suicide prevention programs, improvements to Indian Health Facilities, and home-based care for older adults.

During a recent markup of the FY2024 Transportation-HUD Appropriations bill, House Republicans voted to remove three projects of the 2,680 proposed in the bill. The three targeted projects, requested by Reps. Chrissy Houlahan (D-PA-06), Brendan Boyle (D-PA-01), and Ayanna Pressley (D-MA-07), provide services to the LGBTQ+ community, including housing and meals for older Americans, employment counseling, and vaccines. According to Appropriations Committee Ranking Member Rosa DeLauro, the projects met the committee’s eligibility criteria and “the only reason why they were struck is because of the population it was serving, the LGBTQ community, which is totally discriminatory.”

Policy Riders in FY2024

As we discussed above, policy riders have an incredible impact on communities and often can impede progress and allow members to advance their legislative priorities in an appropriations bill. According to the Clean Budget Coalition, House Republicans added 74 new “poison pill policy riders'' to their proposed FY2024 appropriations bills. These new riders would prohibit Pride flags from being flown over government buildings, block gender-affirming care for veterans, and more. As in the case of the targeted CPFs described above, riders under the new House Republican majority focus heavily on partisan “culture war” issues, including discrimination against LGBTQ+ people. This contrasts considerably with the Senate, where the Appropriations Committee has advanced bills with overwhelming bipartisan support.

Conclusion

Current government funding expires after September 30, 2023. Without new funding bills or a CR, the government will shut down on October 1. However, there will be consequences for federal spending even if Congress passes a CR to avoid a shutdown: the Fiscal Responsibility Act reduces the FY2024 and 2025 defense and non-defense spending caps by one percent if Congress does not pass appropriations bills to fund the government by January 1, 2024 and January 1, 2025, respectively.

Despite this incentive to avoid a CR, at the time of publication, Congress appears far from a compromise that could pass the House and Senate. While the House wages culture wars in its partisan appropriations bills, the Senate has maintained a bipartisan process. Moreover, at the time of publication, only one appropriations bill has passed either the full House or the Senate, despite just two months until a potential government shutdown. On July 27, the House passed H.R. 4366, the Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, 2024, by a vote of 219-211.

Appropriations bills are a critical opportunity for Congress to meet the needs of the moment. From the WIC program to union elections, this process impacts nearly every element of public life. Congress has limited time to determine whether that impact will be helpful or harmful in the coming year.

The Congressional Progressive Caucus Center thanks the Economic Policy Institute and the Clean Budget Coalition for their analyses, which contributed to this piece.